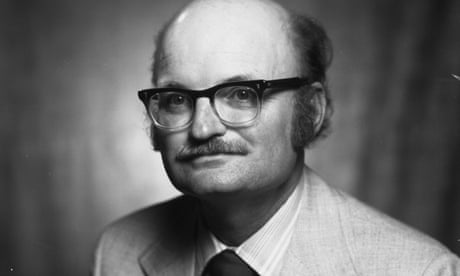

The American novelist John Barth, who has died aged 93, was a noted evangelist for experimental fiction, beguiling his readers with complex stories within stories.

He claimed as his patron saint Scheherazade in the Arabian Nights, the vizier’s daughter whose tales, spun out for 1,001 nights, entranced King Shahryar: “The whole frame of these thousand nights and a night,” Barth said, “speaks to my heart, directly and intimately – and in many ways at once personal and technical.”

He came to notice with his third novel, The Sot-Weed Factor (1960), a riotous mock-epic pastiche that drew upon a satire of American manners of the same title published in 1708 by one Ebenezer Cooke.

Reviewers compared the book to Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, and enjoyed Barth’s rollicking use of coincidence, parody, farce, sentimentality and melodrama. It was much-hyped – “One of the greatest works of fiction of our time,” said the writer and artist Richard Kostelanetz – but Gore Vidal found Barth’s humour to be laboured: “I could not so much as summon up a smile at the lazy jokes and the horrendous pastiche of what Barth takes to be 18th-century English.” Other critics complained of its excessive length, narrow emotional range and an underlying facetiousness in Barth’s tone.

His next novel, Giles Goat-Boy (1966), brought Barth critical and commercial success. It was a mythology drenched campus novel, complete with cold war allegories and self-reflexive narratives, 766 pages long. Barth’s penchant for addressing political, religious and philosophical issues gave his novel a flavour of seriousness that was widely praised. Vidal, however, called it “a book to be taught rather than read”.

The following year, Barth published The Literature of Exhaustion, a manifesto for literary postmodernism, in the Atlantic magazine. The traditional forms of representation were used up, he argued. There were too many contemporary writers who went about their business as though James Joyce, Franz Kafka, Jorge Luis Borges, Samuel Beckett and Vladimir Nabokov had never written. Barth’s impatience with most fiction and his eloquent enthusiasm for the experimental caught a moment in contemporary culture. He became the poster boy for postmodernism.

One of the three children of Georgia (nee Simmons) and John Barth, who ran a sweet shop, he was born in Cambridge, a small crab and oyster town in Maryland, and grew up amid the flat, low-lying tidal marshlands on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay.

His twin sister was whimsically named Jill, and Barth’s family knew him as Jack, a source of teasing during their schooldays.

After graduating from high school, Barth enrolled in a summer programme at the Juilliard School of Music in New York. An enthusiastic jazz drummer, he hoped for a career as an arranger, but at the Juilliard he encountered some seriously talented performers and his ambitions shrank.

Instead, he enrolled at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, to study journalism. He remained at Hopkins to complete a master’s degree, and in 1953 landed a job in the English department at Pennsylvania State University, where he remained for 12 years.

Barth’s first published novel, The Floating Opera (1956), was a traditional first-person narrative about boozing, desire and nihilism on the eastern shore of the Chesapeake. The End of the Road (1958), described by the critic Leslie Fiedler as an example of “provincial American existentialism”, was a darker novel about a grad-school dropout, ending with an abortion. Some of the more gruesome details were cut at the insistence of his publishers, but restored when the novel was later reissued.

In 1965 he took a job teaching at the Buffalo campus of the State University of New York, where he remained until 1973. During that time of student unrest, the campus was repeatedly occupied by local police and troopers of the National Guard. Barth was less sympathetic to the protesters than some of his colleagues, but he wholeheartedly threw himself into the trashing of the practitioners of “traditional” fiction such as John Updike and William Styron, whose work he felt was a literary dead end.

Under the growing influence of Borges and 60s counterculture, Barth turned away from fat pastiche-novels to short fictional forms. Lost in the Funhouse (1968) was a melange of short fictions for print, tape and live voice, which he staged on campuses across the nation. In 1973 he returned to Johns Hopkins to take up a chair of creative writing, and stayed until retirement in 1992.

By the 80s, the frisky, postmodern self-consciousness that had made readers sit up in the 60s had lost some of its capacity to shock. It had gone, within a generation, from being a great cause to a routine, a shtick. Barth’s books increasingly needed to be explained to readers, and sales fell away. Complex, self-referential novels such as Chimera, which shared the National Book Award in 1973, the epistolary Letters (1979) and Sabbatical (1982) were seen as working out the implications of The Literature of Exhaustion.

In 1980 he revisited this essay with The Literature of Replenishment, in which he repented his youthful scorn for the 19th-century novel as practised by the “great premodernists” such as Dickens, Twain and Tolstoy. If, as the modernists asserted, linearity, rationality and consciousness are not the whole story, argued Barth, “we may appreciate that the contraries of those things are not the whole story either … A worthy program for postmodernist fiction, I believe, is the synthesis … of these modes of writing.”

Barth’s essays were collected in three volumes as The Friday Book (1984), Further Fridays (1995) and Final Fridays (2012). A further collection of short nonfiction pieces, Postscripts, was published in 2022. Once Upon a Time (1994), with its teasing promise of tall tales, was his most autobiographical novel. Coming Soon!!! (2001), with its references to The Floating Opera, showed that the old postmodernist playfulness was unquenched.

In 1998, Barth won both the Lannan Foundation’s lifetime achievement award and the Pen/Malamud award for excellence in the short story.

He married Anne Strickland in 1950 and they had three children, Christine, John and Daniel. The couple divorced in 1969 and the following year he married Shelly Rosenberg. She and his children survive him.